Definition

Epistaxis (nosebleed) is a common ear, throat and nose medical emergency. It occurs due to a rupture in a nasal blood vessel or a group of vessels. It can be classified as anterior or posterior nosebleed. Anterior nosebleed is more common but less significant, however posterior nosebleed is less common but more significant. Majority of anterior nosebleeds are identified within Kiesselbach’s plexus (Little’s area) located on the anterior nasal septum. [1]

Introduction to Epistaxis

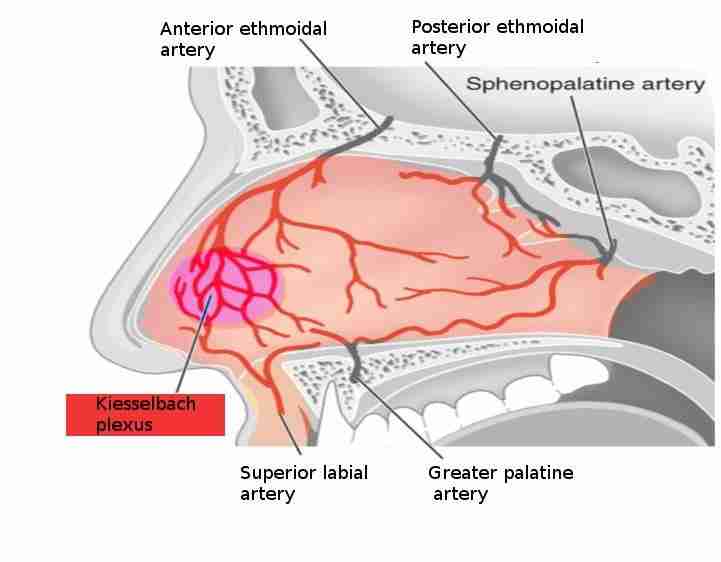

The arterial vasculature of the nasal cavity arises from the terminal branches of five arteries [1].

- Anterior ethmoidal artery

- Posterior ethmoidal artery

- Sphenopalatine artery

- Greater Palatine Artery

- Superior Labial Artery

The watershed of the five main arteries is located at the anterior nasal septum, including Kiesselbach’s plexus (Figure 1.0). The Anterior nasal septum is located at the entrance of the nasal cavity, therefore is subject to environmental triggers such as heat, cold and moisture. This makes it more susceptible to trauma. In addition, the majority of nosebleed takes place at this site, due to the very thin mucosa that lines the septum. Anterior Epistaxis is more commonly reported compared to posterior epistaxis. In addition, anterior nosebleeds are usually caused by local trauma such as rupturing the nasal septum blood vessels by finger scratching or inserting a foreign object in the nostrils. However, if vessels in the posterior or superior nasal cavity bled, posterior epistaxis then occurs. Posterior epistaxis is usually due to systemic causes, such as hypertension or coagulopathies and is more reported by adults.[1][2][3]

Pathophysiology

Epistaxis results from a rupture in a blood vessel in the nasal mucosa. This usually happens due to trauma. Since thin mucosa lines up the Anterior nasal septum, the blood vessel becomes highly susceptible to injury. The bleeding can be spontaneous, medication induced or secondary to a comorbidity such as hypertension or melanoma. Bleeding due to trauma is usually acute and resolves on its own. However, when a comorbidity is involved, the bleeding can be more serious. Specific medications can increase the chance of nosebleed. It is usually assumed that posterior nosebleeds take place at terminal branches of the sphenopalatine and posterior ethmoidal arteries named Woodruff’s plexus. Blood can enter the nasopharynx, which is then swallowed and can be coughed. Posterior epistaxis is usually harder to control due to the high blood flow compared to anterior epistaxis. [1]

Etiology

There are a plethora of causes to nosebleed. The causes include, but are not limited to systemic, local, medication-induced and environmental [1]. While the ones mentioned below are the most common causes of epistaxis, rarer etiologies such as neoplasms and malformations should be considered in the diagnosis. [4][5][6]

Local Causes

- Self-inflicted trauma and accidental trauma (Nose punch, Inserting a finger in the nostrils)

- Chronic nasal cannula use

- Anatomic deformities (Deviated septum, Vascular malformations)

Inflammation

- respiratory infections (influenza virus, common cold)

- Allergies

Systemic Causes

- Hypertension (commonly in posterior Epistaxis)

- Coagulopathies (Leukemia, von Willebrand disease, hemophilia, Thrombocytopenia)

- Alcoholism

Environmental Factors

- Weather dryness

- Cold weather

- Low humidity

Medication Induced

- Anticoagulants (warfarin, heparin)

- Topical nasal steroid sprays (Prolonged use)

- NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, aspirin)

- Illicit drugs (cocaine)

- Platelet aggregation inhibitors (clopidogrel)

Tumors and Aneurysms

Juvenile angiofibromas

- malignant melanoma

- squamous cell carcinoma

- Aneurysms

(Cho and Tabassom. StatPearls Publishing.2021)

Visual Representations

Figure 1.0: The five arteries that supply the anterior nasal septum. Kiesselbach plexus is a common site of anterior epistaxis. (S Bhimji MD, StatPearls Publishing LLC.) [1]

Figure 2.0: The main symptom of epistaxis is bleeding from the nostrils. The blood flow can range from drops to a stream of blood based on the severity and the location of the ruptured blood vessel. 90% of anterior epistaxis is due to trauma within Kiesselbach’s plexus [1]. ( https://www.pexels.com/photo/2-men-boxing-on-ring-70567/ ) (License:https://www.pexels.com/creative-commons-images/ )

Differential Diagnosis:

In the presence of nosebleed, it is necessary to perform a differential diagnosis by an accurate history, physical examination and diagnostic tests. If the bleeding is very significant, it is necessary to first stop the bleeding and stabilize the patient.

- The history should attempt to determine which side the bleeding began, making it a point to direct the physical examination

- In addition, the duration of bleeding should be established, as well as any triggering events.

- The time and number of previous nosebleeds and their resolution should also be identified

- The history should highlight any bleeding disorders (including familiarity) and conditions associated with platelet or coagulation defects

- The pharmacologic history should specifically investigate the use of medications that may promote bleeding.

- During active bleeding, inspection could be difficult, so attempts are first made to stop the bleeding.

- The nose is then examined using a nasal speculum and a headlamp or a frontal mirror, which leaves one hand free to hold the aspirator or another instrument.

- Anterior bleeding sites are usually evident on direct examination. If bleeding is severe or recurrent and no bleeding site is observed, optical fiber endoscopy may be necessary.

- Routine laboratory tests are not required for diagnosing epistaxis. Patients with symptoms or signs of a bleeding disorder and those with severe or recurrent epistaxis should undergo a Complete Blood Count (CBC), prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time. CT may be performed if a foreign body, tumor, or sinusitis is suspected. Management will depend on the severity of the bleeding and the patient’s concomitant medical problems.

Key Differences between Anterior and Posterior Nosebleed

Anterior Epistaxis

- The blood flow is usually weak and stops on its own

- More likely happening in children and teens

- More common form of epistaxis

- Mainly due to trauma to the anterior nasal septum (face punch, nose picking, inserting a foreign object in the nostrils)

- Most of the time it is not a serious condition

- Laboratory tests should be conducted to rule out any more significant cause if the blood flow is strong and posterior epistaxis should be suspected.

Posterior Epistaxis

- Less common but more serious

- Can be due to hypertension

- Can order tests to check for blood clotting disorders

- Can be due to taking anticoagulants (heparin)

(Cho and Tabassom. StatPearls Publishing.2021)

Diagnosis

- Detailed history assessment is a must

- Establishing a timeline of the condition and how frequent and intense is the bleeding.

- Asking about other comorbidities or other secondary symptoms.

- fluid resuscitation and volume replacement therapy can be viewed as an option after careful examination and a detailed look at the history of the patient

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) and coagulation panel can be ordered

(Ayesha Tabassom & Julia J. Cho. StatPearls Publishing.2021)

Physical Examination

- Reviewing the patient’s medical history.

- Duration of the bleeding

- Severity

- Frequency

- Unilateral or bilateral bleeding

- The history of drug/Alcohol use or abuse

- The history of using anticoagulants or NSAIDs

- Family history; vascular disease or hypertension

- Preparing PPE and diagnostic equipment such as headlamp for the physical exam

- nasal speculum

- headlamp,

- packing,

- cotton pledgets

- silver nitrate swabs

- bayonet forceps

- and topical vasoconstrictors

- anesthetic

- the patient should be seated in the exam chair, in a room that have suctions available, in case a clot needs to be removed from the nasal cavity

- speculum can be used to visualize the bleeding location

- In case the location of the bleeding is not easily visualized, endoscopy can be used

(Cho and Tabassom. StatPearls Publishing.2021)

Management and Treatment

Anterior Epistaxis

- Anterior nose bleeding can be resolved on its own

- Monitor oxygen levels and hemodynamic stability

- Minimal pressure on the nose can also help stop the anterior bleeding (10 minutes)

- blood clots in the nasal cavity should be removed by suction before treatment

- vasoconstrictors (ex. Oxymetazoline) can be used to reduce the bleeding

- cautery can be used, using silver nitrate sticks if topical treatment did not work

- Packing can be used in cases of posterior and anterior epistaxis

- in case that cautery did not work, anterior nasal packing should be the next option on the list (refer to the additional reference section for articles on nasal packing)

- packing can be performed using nasal tampons lubricated with antibiotic ointments

Posterior Epistaxis

- if bleeding is severe and continuous and none of the above treatments work, posterior epistaxis is suggested

- bleeding from both nostrils, coughing blood,

- longer posterior tampons can be used that can help cease the bleeding

(Cho and Tabassom. StatPearls Publishing.2021)

Additional Resources and Clinical Studies:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5778404/ (A comprehensive overview)

Fishman J, Fisher E, Hussain M. Epistaxis audit revisited. J Laryngol Otol. 2018 Dec;132(12):1045

Send T, Bertlich M, Eichhorn KW, Ganschow R, Schafigh D, Horlbeck F, Bootz F, Jakob M. Etiology, Management, and Outcome of Pediatric Epistaxis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Jan 07; [PubMed]

Kitamura T, Takenaka Y, Takeda K, Oya R, Ashida N, Shimizu K, Takemura K, Yamamoto Y, Uno A. Sphenopalatine artery surgery for refractory idiopathic epistaxis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2019 Aug;129(8):1731-1736. [PubMed]

Keen MS, Moran WJ. Control of epistaxis in the multiple trauma patient. Laryngoscope 1985; 95: 874– 5.

Herkner H, Laggner AN, Müllner M et al. Hypertension in patients presenting with epistaxis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2000; 35: 126–30

M Middleton, Paul. “Epistaxis.” Emergency Medicine Australasia 16.5-6 (2004): 428-40. Print.

McGarry GW, Gatehouse S, Hinnie J. Relation between alcohol and nose bleeds. BMJ 1994; 309: 640.

Watson MG, Shenoi PM. Drug‐induced epistaxis? J. R. Soc. Med. 1990; 83: 162– 4.

INTEGRATE (UK National ENT research trainee network) on its behalf: Mehta N, Stevens K, Smith ME, Williams RJ, Ellis M, Hardman JC, Hopkins C. National prospective observational study of inpatient management of adults with epistaxis - a National Trainee Research Collaborative delivered investigation. Rhinology. 2019 Jun 01;57(3):180-189. [PubMed]

Clark M, Berry P, Martin S, Harris N, Sprecher D, Olitsky S, Hoag JB. Nosebleeds in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Development of a patient-completed daily eDiary. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018 Dec;3(6):439-445. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Ramasamy V, Nadarajah S. The hazards of impacted alkaline battery in the nose. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018 Sep-Oct;7(5):1083-1085. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Alvi A, Joyner‐Triplett N. Acute epistaxis: How to spot the source and stop the flow. Postgrad. Med. 1996; 99: 83– 96

Keen MS, Moran WJ. Control of epistaxis in the multiple trauma patient. Laryngoscope 1985; 95: 874– 5

Chiu, T. W., Shaw-Dunn, J., & McGarry, G. W. (2008). Woodruff’s plexus. The Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 122(10), 1074-7. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S002221510800176X

Krulewitz NA, Fix ML. Epistaxis. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019 Feb;37(1):29-39. doi:1016/j.emc.2018.09.005. PMID: 30454778.

Yau S. An update on epistaxis. Aust Fam Physician. 2015 Sep;44(9):653-6. PMID: 26488045

Middleton PM. Epistaxis. Emerg Med Australas. 2004 Oct-Dec;16(5-6):428-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2004.00646.x. PMID: 15537406

Teymoortash A, Sesterhenn A, Kress R, et al: Efficacy of ice packs in the management of epistaxis. Clin Otolaryngol 28:545, 2003.

Duncan IC, Fourie PA, Ie Grange CE, et al: Endovascular treatment of intractable epistaxis—Results of a 4-year local audit. S. (Afr Med J 94:373, 2004)

Viducich RA, Blanda MP, Gerson LW. Posterior epistaxis: clinical features and acute complications. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1995; 25: 592– 6

Beck R, Sorge M, Schneider A, Dietz A. Current Approaches to Epistaxis Treatment in Primary and Secondary Care. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(1-02):12-22. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0012

Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR: Oral and Maxillofacial Infections (ed 4), Philadelphia, PA, WB Saunders, 2002

Hashmi SM, Gopaul SR, Prinsley PR, et al: Swallowed nasal pack: A rare but serious complication of the management of epistaxis. J Laryngol Otol 118:372, 2004)

Prepageran N, Krishnan G: Endoscopic coagulation of sphenopalatine artery for posterior epistaxis. Singapore Med J 44:123,2003

(Jones GL, Browning S, Phillipps J, et al: The value of coagulation profiles in epistaxis management. Int J Clin Pract 57:577, 2003

American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support, 6th edn. Chicago: American College of Surgeons, 1997.

London SD. A reliable medical treatment for recurrent mild anterior epistaxis. Laryngoscope 1999; 109: 1535– 7.

Peretta LJ, Denslow BL, Brown CG. Emergency evaluation and management of epistaxis. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 1987; 5: 265– 77.

Krempl GA, Noorily AD. Use of oxymetazoline in the management of epistaxis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1995; 104: 704– 6.

Tomkinson A, Bremmer‐Smith A, Craven C, Roblin DG. Hospital epistaxis rate and ambient temperature. Clin. Otolaryngol. 1995; 20: 239– 40.

Herkner H, Laggner AN, Müllner M et al. Hypertension in patients presenting with epistaxis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2000; 35: 126– 30.

Ruddy J, Proops DW, Pearman K, Ruddy H. Management of epistaxis in children. Int. J. Ped. Otorhinolaryngol. 1991; 21: 139– 42.

References

- Epistaxis

Ayesha Tabassom; Julia J. Cho. Published on 2020 Aug 8 by StatPearls Publishing - Etiology, Management, and Outcome of Pediatric Epistaxis

Send T, Bertlich M, Eichhorn KW, Ganschow R, Schafigh D, Horlbeck F, Bootz F, Jakob M. Published on 2019 Jan 07 by PubMed - Sphenopalatine artery surgery for refractory idiopathic epistaxis: Systematic review and meta-analysis

Kitamura T, Takenaka Y, Takeda K, Oya R, Ashida N, Shimizu K, Takemura K, Yamamoto Y, Uno A. Published on 2019 Aug by PubMed - National prospective observational study of inpatient management of adults with epistaxis - a National Trainee Research Collaborative delivered investigation

INTEGRATE (UK National ENT research trainee network) on its behalf: Mehta N, Stevens K, Smith ME, Williams RJ, Ellis M, Hardman JC, Hopkins C. Published on 2019 Jun 01 by PubMed - Nosebleeds in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Development of a patient-completed daily eDiary

Clark M, Berry P, Martin S, Harris N, Sprecher D, Olitsky S, Hoag JB. Published on 2018 Dec by PMC - The hazards of impacted alkaline battery in the nose

Ramasamy V, Nadarajah S. Published on 2018 Sep-Oct by PMC